For years, holding rental properties in your personal name was the default for UK landlords. It was simple, straightforward, and made perfect sense. But the game has changed, and what was once the standard approach can now be a serious drag on your profits.

Many landlords are now making the strategic switch to transfer their properties into a limited company. This isn't just about tweaking a few numbers; it's a fundamental shift in how you structure your property business, driven almost entirely by major changes to UK tax laws—specifically, the infamous Section 24.

The short answer? Tax efficiency. The long answer is a bit more nuanced, but it all comes back to protecting your bottom line.

The real tipping point was the government's phasing out of mortgage interest relief for individual landlords. You probably remember the old system: you could deduct every penny of your mortgage interest from your rental income before the taxman got his slice. Simple. Fair.

That's all gone. Now, as a personal landlord, you only get a basic rate tax credit of 20% on your mortgage interest. For higher-rate taxpayers, this was a bombshell. It artificially inflates your taxable income, pushing many into a higher tax bracket without them actually earning a penny more.

This isn’t just a feeling; the numbers back it up. The wave of incorporations has been massive. By 2021, the number of buy-to-let companies in the UK had soared to 269,300—more than double what it was just four years earlier. That surge started right after the 2017 tax changes kicked in. You can dig into the data on this trend, and it paints a very clear picture.

To really get a handle on why this is happening, it helps to see the two ownership models side-by-side. The contrast, especially when it comes to tax treatment, is pretty stark.

Looking at this, you can immediately see the appeal. For a limited company, mortgage interest is just another business cost, treated exactly as it should be.

Let’s put some real numbers on this. Imagine Sarah, a landlord paying the 40% higher rate of tax. She has a property that brings in £15,000 a year in rent, with annual mortgage interest costs of £8,000.

As a personal landlord: Sarah can't deduct the £8,000 interest. She's taxed at 40% on the full £15,000 rent (£6,000 tax). Then, she gets her 20% tax credit on the interest (£1,600). Her final tax bill is a painful £4,400.

As a limited company: The company treats the £8,000 interest as an expense. This leaves a taxable profit of £7,000. It pays Corporation Tax on this (we'll use 19% for this example), making the tax bill just £1,330.

The difference is staggering. Sarah saves over £3,000 in tax every single year just by holding the property in a company. That's money that can stay in the business to cover repairs, save for a new deposit, or pay down loans.

But it’s not just about the tax savings today. Operating through a limited company draws a clean line between your personal assets and your business liabilities. It provides a professional structure that's built for growth and makes future succession planning much smoother. For any serious investor looking to scale their portfolio, it's a move you can't afford to ignore.

Before any deeds change hands, you first need to build a solid corporate foundation for your property investments. This isn't the time to grab a generic, off-the-shelf company. For property, the structure needs to be deliberate and fit-for-purpose right from the start.

The go-to corporate structure for this is almost always a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) limited company. An SPV is just a company set up for one specific reason—in our case, to own and manage property. This laser focus is exactly what mortgage lenders want to see. It neatly separates your property portfolio from any other business ventures, which makes their risk assessment a whole lot simpler.

Setting up an SPV through Companies House is pretty straightforward, but you have to be precise. One of the most common tripwires is selecting the right Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) code. This little number tells HMRC and, crucially, lenders what your company actually does.

For property investment, you’ll likely be using one of these three codes:

Nailing the SIC code is absolutely vital. If you get this wrong, you're creating a massive headache for yourself when you apply for a mortgage. Lenders will immediately flag a company that isn't properly classified for property investment, and your application will grind to a halt.

Expert Tip: Don't just rush through the company formation process. Double-check every single detail, from the director's information right down to the SIC code. A simple admin slip-up here can snowball into serious delays and extra costs when you're trying to deal with solicitors and lenders.

Once your company is officially registered, you have a legal entity that's ready to start owning assets. Now, it's time to get into the legal mechanics of actually moving the property out of your personal name and into the company's.

This is where a specialist conveyancing solicitor becomes worth their weight in gold. Transferring property to a limited company isn't just a bit of paperwork; it's legally treated as a full-blown sale and purchase transaction. Your solicitor is the one who will navigate all the legal complexities to make it happen.

Here’s what they’ll be handling:

It's really important to realise that not all solicitors are created equal. You need someone who has specific experience with these corporate transfers, understands the world of SPVs, and knows what commercial mortgage lenders are looking for. Our guide on buying a house via a limited company goes into a bit more detail on this side of things.

Ultimately, getting expert legal and accounting advice from day one is non-negotiable. An accountant will help structure the transfer to be as tax-efficient as possible, while a solicitor makes sure the entire legal process is completely watertight. Trying to cut corners here is a false economy that almost always ends in costly tax blunders and legal tangles.

Moving your properties from personal to corporate ownership isn't just a paper-shuffling exercise. In the eyes of HMRC, you're effectively selling the property to your company. That's a critical distinction because it immediately flags two major taxes: Capital Gains Tax (CGT) and Stamp Duty Land Tax (SDLT).

Getting your head around these from the start is absolutely essential. If you don't, what looks like a savvy long-term strategy can quickly become a short-term financial headache. The costs are very real, they're immediate, and they can be punishing if you haven't planned properly.

Capital Gains Tax is levied on the profit you make when you 'dispose' of an asset that's gone up in value. When you transfer a property to your company, HMRC sees this as a disposal, even if no actual money changes hands.

The "gain" is simply the difference between the property's market value now and what you originally paid for it. If you've held the property for a good few years, that gain could be massive, landing you with a hefty personal CGT bill.

Thankfully, there's a powerful tool that can defer this tax: Incorporation Relief. For portfolio landlords, this relief is a complete game-changer, but it doesn't come easy. The rules are strict.

Crucially, you can only claim it if you're transferring a genuine property business into the company, not just a single investment property.

The landmark legal case of Ramsay vs HMRC is the one everyone refers to here. The tribunal sided with HMRC, ruling that Mrs Ramsay's single property transfer didn't count as an active "business." To stand a chance, you need to show a significant level of management activity.

To build a solid case that you're running a business, you'll need to demonstrate a few things:

If you tick these boxes and successfully claim Incorporation Relief, you won't pay any CGT when you transfer. Instead, the gain is "rolled over" into the shares of your new company. The tax is essentially kicked down the road until you one day sell those shares, which could be years away.

Key Takeaway: Incorporation Relief is not a given. You must prove to HMRC that you're transferring a legitimate, active property business. Keeping detailed records of your management hours and activities is absolutely vital.

While you might be able to swerve the immediate CGT bill, Stamp Duty Land Tax (SDLT) is another beast entirely. Your company is legally buying the property from you at its current market value, and SDLT must be paid on that figure.

Here's the kicker: because the buyer is a company acquiring a residential property, it will almost certainly be hit with the 3% surcharge for additional dwellings. This applies even if it's the very first property the company owns.

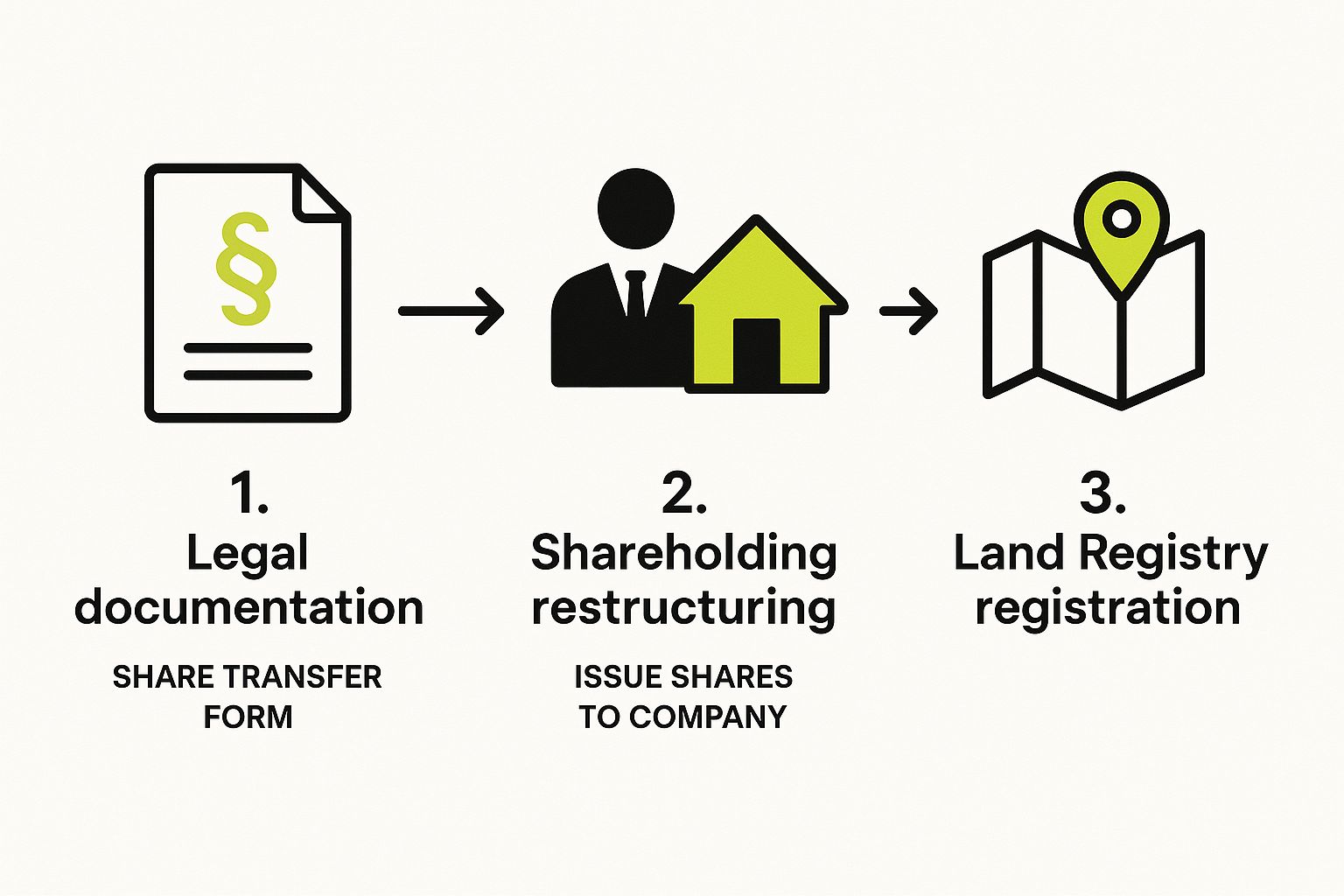

This infographic breaks down the core legal steps in the transfer, showing where tax liabilities like SDLT fit into the picture.

As you can see, once the legal paperwork is sorted, the final step is registering the change with the Land Registry. This is what makes the company's ownership official and crystallises the transaction on which SDLT is owed.

Let's put some numbers on this. Say you're transferring a property valued at £400,000 into your new limited company.

Based on the current SDLT rates in England, your company's bill would look something like this:

That £19,500 is a direct, upfront cost the company needs to find the cash for. It’s often one of the biggest initial hurdles landlords face. On higher-value properties, the bill climbs rapidly. In fact, research shows that for properties over £500,000, companies can face an effective SDLT rate of up to 17% once the surcharge is added. It's a major financial consideration.

Forecasting these tax costs with accuracy is non-negotiable. You'll need specialist advice to make sure your numbers are right and that you have the cash ready to complete the transfer. For more detailed guidance, check out our insights on managing your https://www.gentax.uk/services/property-business-accounts.

One of the biggest practical hurdles when moving property into a limited company is always the mortgage. A common myth I hear is that you can just 'novate' or transfer your personal buy-to-let mortgage over to the company. If only it were that simple.

Legally, the whole process is treated as a sale and purchase. Your company has to get its own commercial mortgage to effectively 'buy' the property from you. The money from this new loan is then used to pay off your original personal mortgage. This means you’ll be diving into the world of limited company mortgages, which play by a completely different set of rules.

Lenders see lending to a company as a different kettle of fish compared to lending to an individual. This really shows in the types of products they offer and the criteria they use. You need to be ready for a few key differences.

For starters, interest rates on limited company mortgages are often a touch higher than their personal BTL counterparts. Lenders also tend to be stricter with their stress testing and affordability calculations. Their main focus is making sure the property's rental income covers the mortgage payments by a comfortable margin.

On top of that, arrangement fees can be much heftier, often calculated as a percentage of the loan amount rather than a flat fee. It’s a significant upfront cost you absolutely must factor into your budget for the transfer. Knowing about these quirks from the get-go will make the whole thing a lot less painful.

To get the green light for finance, you need to present your company as a slick, professional operation. Lenders will pick apart your application, so having all your ducks in a row is non-negotiable. A solid property business plan isn't a 'nice-to-have' anymore; it's essential.

Your business plan should lay out:

Presenting this information professionally signals to lenders that you’re serious and you understand what you're getting into. It shows this isn't just a side hustle but a structured business. For some wider guidance on business finances, our article on tax advice for small businesses is a great place to start.

A classic mistake is underestimating the sheer volume of paperwork required. Lenders will want to see everything from company formation documents and business bank statements to your personal financial history. Start gathering these documents early to avoid a last-minute panic.

Here's something that often catches landlords by surprise. Even though you're setting up a limited company for that legal separation, lenders will almost always demand a personal guarantee from the directors.

A personal guarantee is a legally binding promise. It means that if the company fails to make its mortgage payments, you, the individual, are personally on the hook for the debt. This essentially pierces the "limited liability" veil for the mortgage, giving the lender that extra layer of security they need.

It might seem counterintuitive, but it's standard practice in commercial lending. Lenders want to know the people behind the company have skin in the game. Trying to refuse a personal guarantee will almost certainly mean your mortgage application gets rejected. Understanding this from the outset leads to much more productive conversations with brokers and helps you manage your own personal risk.

Getting your property portfolio successfully transferred is a massive achievement, but it’s also where the real work begins. This move fundamentally changes your day-to-day financial world. The tax advantages are what draw most landlords in, but they come hand-in-hand with a much more formal and structured set of responsibilities. Your finances are no longer personal; they're corporate.

The biggest upside is how the company handles its profits. Holding onto earnings within the business to fund future purchases or pay down debt becomes far more efficient. Instead of you personally paying income tax on all your rental profits, the company pays Corporation Tax, which is often a friendlier rate.

This tax difference is what creates a powerful engine for growth. Think about it: since April 2020, individual landlords have had their mortgage interest relief slashed to a basic 20% tax credit. This change really hits higher-rate taxpayers hard. A limited company, in stark contrast, can still deduct the full mortgage interest as a standard business expense.

When you also remember that personal landlords can pay up to 45% income tax on their profits, while a company pays Corporation Tax (starting at just 19% on profits up to £50,000), the advantage is crystal clear. You can see the data on this landlord incorporation trend here for more context.

While keeping profits in the business is great for expansion, you'll eventually want to access that money for yourself. You can't just take cash from the business account anymore. Every single withdrawal has to be properly recorded and categorised, and there are three main ways to do it, each with its own tax implications.

Crucial Insight: One of the biggest mistakes you can make is mixing your personal and business funds. The company absolutely must have its own dedicated bank account. All rental income goes in, and all property expenses come out of that account. This financial separation is completely non-negotiable.

With greater financial power comes greater responsibility. Running a limited company brings a significant step-up in admin compared to being a sole trader landlord. It's the trade-off for the tax perks and liability protection.

You are now legally required to keep accurate, detailed company records. This isn't just good practice—it's a legal duty enforced by both Companies House and HMRC.

Here’s a quick look at your new annual compliance checklist:

Missing these deadlines leads to automatic financial penalties and, in serious cases, can even result in legal action against the directors. The admin burden is very real, which is why almost every landlord operating this way hires an accountant to handle the compliance side of things. It ensures everything is filed correctly, on time, and without the headache.

Even with a solid plan, the process of moving property into a limited company always throws up a few practical questions. Thinking through these 'what ifs' is essential for a smooth transition, helping you sidestep any nasty legal or financial surprises down the line.

Let's walk through some of the most common queries we hear from landlords taking this step. Getting these details ironed out from the start means your new company will be compliant and tax-efficient right out of the gate, saving you from costly fixes later on.

While you technically can, it's rarely a good idea. Moving just a single property creates a couple of major headaches.

The biggest hurdle is Capital Gains Tax. To get your hands on the incredibly useful Incorporation Relief (which lets you defer CGT), HMRC needs to see that you're transferring an actual 'business' into the company, not just a standalone asset. It's tough to argue that a single property counts as a business, making it very likely you'll face a hefty, immediate CGT bill on your gains.

On top of that, the costs involved—legal fees, mortgage arrangement fees, valuations—are pretty much fixed. When you spread those expenses across just one property, the cost per property becomes eye-wateringly high. It's vital to sit down with an advisor and crunch the numbers to see if the long-term tax savings really do outweigh such significant upfront costs for a single rental.

This is a big concern for many landlords: what happens to all the equity you’ve painstakingly built up? The good news is it doesn't vanish. It just changes its form.

When the property is transferred, your equity is converted into value held by the company. Say you transfer a property worth £300,000 with a £200,000 personal mortgage still on it. Your £100,000 of equity is now an asset of the new company.

This value is usually recorded on the company's books as a Director's Loan. In simple terms, this means the company now officially owes you, the director, £100,000. This is a brilliant tool, as it often allows you to draw that money out of the company over time without paying personal income tax on it. Just make sure your accountant logs this correctly to keep the books straight.

Absolutely. This isn't just good manners—it’s a legal must. As soon as the property title moves over to your limited company, the legal landlord has changed.

You are required to inform your tenants in writing, giving them the company’s full name and registered address as their new landlord. This is a formal notice under Section 3 of the Landlord and Tenant Act 1985.

But it doesn't stop there. You also need to tackle these key admin tasks:

Dropping the ball on these communications and legal updates can lead to some serious financial penalties and legal trouble. It's a non-negotiable part of the process that proves your professionalism and ensures you're ticking all the right boxes. Once you're set up, getting expert advice on the accounting for limited companies is the natural next step.

Ready to structure your property business for optimal growth and tax efficiency? The team at GenTax Accountants specialises in helping landlords navigate the complexities of incorporation and ongoing financial management. Book your free consultation today to see how our expert, tech-driven service can save you time and money.