Deciding to close your company is a big step, but it’s not always a sign of failure. In fact, many successful businesses reach a natural conclusion, whether that's due to retirement, a change in direction, or simply because a project has run its course.

Whatever the reason, it's worth taking a moment to be sure this is the right path before you get tangled up in the paperwork. The first, most important question to answer is about your company's financial health.

Put simply: can your business pay all of its debts? Your answer to this single question will determine the entire legal process you need to follow.

A solvent company is one with enough assets to cover all its liabilities. This means it can comfortably pay everyone it owes money to, including HMRC, within 12 months. If your company is in the black, you’ll generally have a much simpler, more direct route to closure.

On the other hand, an insolvent company can't meet its financial obligations. Its debts are greater than its assets, and it can’t pay creditors when payments are due. Trying to close an insolvent company using the wrong method can lead to serious legal trouble for the directors, so getting this right is crucial.

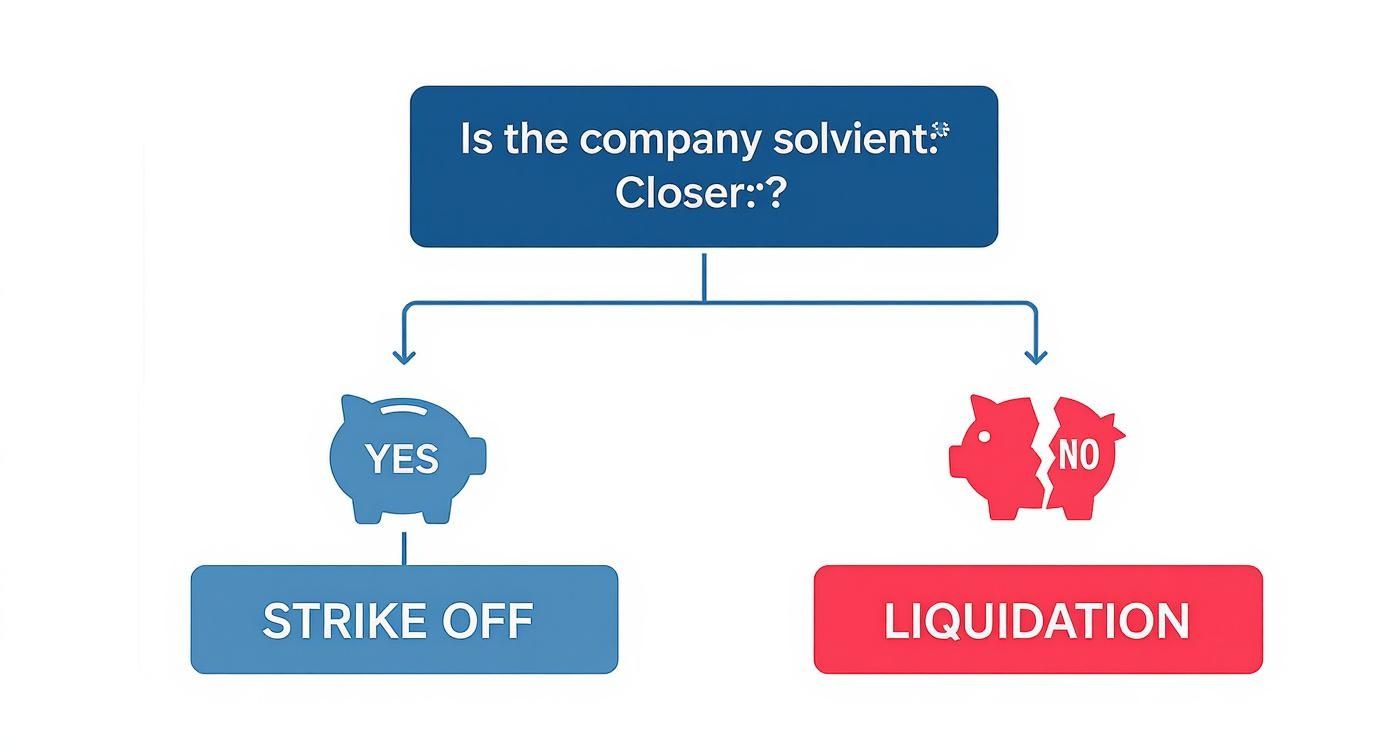

This decision tree shows you the two main paths, depending on whether your company is solvent or not.

As you can see, solvency is the clear dividing line between a straightforward strike-off and a more formal liquidation. It's the factor that guides you towards the legally correct procedure.

Once you've figured out where your company stands financially, you can look at the two main ways to close it down. Each route is designed for a completely different scenario.

Striking Off (or Dissolution): This is the most common and cheapest way to close a solvent company that has stopped trading. It involves applying to Companies House to have the business name removed from the official register. It's the perfect option for businesses with few or no assets left to distribute.

Liquidation: This is a much more formal and legally complex process that has to be overseen by a licensed insolvency practitioner. It's a legal requirement for insolvent companies, but it's also a very tax-efficient option for solvent companies that have significant assets to distribute among shareholders.

For a clearer picture, here’s a quick comparison of the two options. The key takeaway is that your company's solvency dictates which path you can take.

This table highlights just how different the two processes are. A simple strike-off is managed by the directors, whereas liquidation brings in a formal third party to handle everything.

A common misconception is that closing a company is always difficult and expensive. For many small businesses, a voluntary strike-off is a straightforward process costing as little as £33.00 in filing fees, provided all legal duties are met correctly.

Choosing the right path isn't just about ticking boxes for compliance; it's about ensuring a clean and final end to your business's legal and financial responsibilities. For tailored advice on navigating the financial requirements for limited companies, getting professional guidance can prevent costly mistakes.

Making an informed choice now will save you time, money, and potential legal headaches down the line.

For a lot of solvent companies that have run their course, getting struck off the register is the most straightforward and cheapest way to close up shop. This process, also called voluntary dissolution, officially wipes your company's name from the Companies House register. At that point, it legally ceases to exist. It's a move led by the directors and is perfect for businesses without complicated financial loose ends.

The key document in all this is the DS01 form. Think of it as your formal application to Companies House, letting them know you intend to dissolve the company. Getting this form right is the first big hurdle to a clean closure.

Before you even think about filling out the DS01, your company has to tick a few boxes. Companies House has strict rules in place, mainly to protect creditors and make sure the process isn't being used to duck responsibilities.

The biggest requirement? The company must have stopped all business activities for at least three months. That means no trading, no selling off the last bits of stock, and not even changing the company name during this period. Your business has to be, for all intents and purposes, dormant.

On top of that, your company can't be tangled up in any insolvency proceedings, like liquidation. Trying to strike off an insolvent company is a serious offence, and the consequences for directors can be severe.

Once you’re sure your company qualifies, it's time to tackle the application. You can file the DS01 form online for a fee of £33.00, which is a good bit cheaper than the old paper-filing route. To do it online, you'll need your Companies House authentication code. It’s vital to have solid security measures in place, like those needed for Companies House ID verification, when you're handling sensitive filings like this.

A majority of the company's directors must sign the application. Simple enough if there are two of you – both must sign. If there are more than two, a simple majority will do. This is a common trip-up; one director can't just decide to shut things down on their own if the others aren't on board.

Here's what the official government guidance on the DS01 form looks like.

This document walks you through the entire procedure, highlighting the legal duties and steps directors need to follow to avoid having the application rejected or facing penalties.

This is probably the most critical part of the process, and it's the one people most often get wrong. Within seven days of submitting your DS01 application, you are legally required to send a copy to all "interested parties." This isn't just red tape; it ensures everyone with a stake in the company gets a fair chance to object.

So, who are these interested parties? The list is quite specific:

Failing to notify these parties is a criminal offence. It can lead to a hefty fine, imprisonment for the directors, or even both. This step demands your full attention.

This notification rule is exactly why you have to settle all your debts before you apply. If a creditor finds out you're dissolving while they're still owed money, they will almost certainly file an objection with Companies House. That will bring the whole process to a screeching halt.

Once Companies House accepts your DS01 application, things go public. A notice will be published in The Gazette, which is the UK's official public record. This acts as a final public announcement that you're planning to dissolve the company.

This notice kicks off a two-month waiting period. During this time, any interested party can formally object to the strike-off. The most common reasons for an objection are an unpaid debt or an ongoing legal dispute.

If no objections are raised within that two-month window, Companies House will publish a second and final notice in The Gazette. This notice confirms that the company has been dissolved. From that moment on, the company no longer exists as a legal entity, and its name is removed from the official register.

While a simple strike-off works for straightforward, solvent companies, liquidation is the more formal and structured path you’ll need to take in complex situations. Don't think of it as just a tool for businesses in financial trouble; it's also an incredibly effective way for solvent companies with significant assets to close down efficiently.

At its core, liquidation means appointing a licensed insolvency practitioner. Their job is to formally wind up the company’s affairs, sell off its assets, and then distribute whatever cash is raised. The process splits into two very different paths, depending entirely on one crucial question: is the company solvent or insolvent?

A Members' Voluntary Liquidation, or MVL, is a process designed for solvent companies looking to close down in a highly tax-efficient way. It’s often the go-to option when the business has retained profits and assets worth more than £25,000 to distribute among its shareholders.

The biggest win with an MVL is how HMRC treats the final payouts. Instead of being taxed as dividend income—which could see you paying rates as high as 39.35%—the funds are treated as a capital gain. This is where the real tax savings kick in.

Many directors and shareholders can take advantage of Business Asset Disposal Relief (BADR). This handy relief slashes the Capital Gains Tax rate to a flat 10% on qualifying assets, right up to a lifetime limit of £1 million. To qualify, you generally need to have been an employee or director and held at least 5% of the company’s shares for a minimum of two years.

An MVL can lead to massive tax savings, but it's not something you can do yourself. The law is clear: you must appoint a licensed insolvency practitioner to manage the entire process, from the initial declarations right through to the final distribution of assets.

The process kicks off when the directors make a formal Declaration of Solvency. This is a serious legal statement confirming the company can pay all its debts, with interest, within 12 months. Take this step seriously. A false declaration can lead to hefty fines or even a prison sentence, so getting the numbers right is absolutely vital.

When a company is insolvent—meaning it can't pay its debts as they become due—the directors' legal duties shift. They must act in the best interests of the creditors. If you know the company is insolvent but continue to trade, you could face accusations of wrongful trading, which comes with severe personal liability.

In this situation, the responsible—and legally required—route is a Creditors' Voluntary Liquidation (CVL).

A CVL is started by the company's directors and shareholders, who formally acknowledge the dire financial position and agree to put the company into liquidation. Just like an MVL, a licensed insolvency practitioner has to be appointed to act as the liquidator.

Their role is to take control, sell the company's assets for the best price possible, and distribute the proceeds to creditors in a specific, legally-defined order. This ensures an orderly and fair wind-down, and it protects directors from further liability, provided they’ve acted correctly up to that point.

When a CVL is on the horizon, a director's responsibilities change dramatically. Your primary duty is no longer to the shareholders; it's to the company's creditors.

This means you must:

Taking these steps shows you're acting responsibly and helps shield you from potential legal trouble down the line. For directors navigating these tricky financial waters, getting support from a fractional finance director can provide the expert guidance needed to make sound decisions during such a critical period.

For a broader perspective on winding down any type of business, including the legal and financial steps involved, you might find this guide on the steps to close down a business helpful. Choosing the right liquidation path isn’t just about ticking boxes; it's a critical decision that protects directors, fulfils legal duties, and makes sure the company is closed correctly and ethically.

Telling Companies House you’re closing down is one thing, but settling your affairs with HMRC is a whole other, and arguably more critical, final step. Getting this part wrong can lead to penalties and complications long after you think you’ve closed the doors for good.

Think of this as your financial closure checklist. Ticking these boxes ensures a clean break, preventing HMRC from chasing you for returns or payments for a company that no longer exists. It’s all about closing the books correctly to protect yourself as a director.

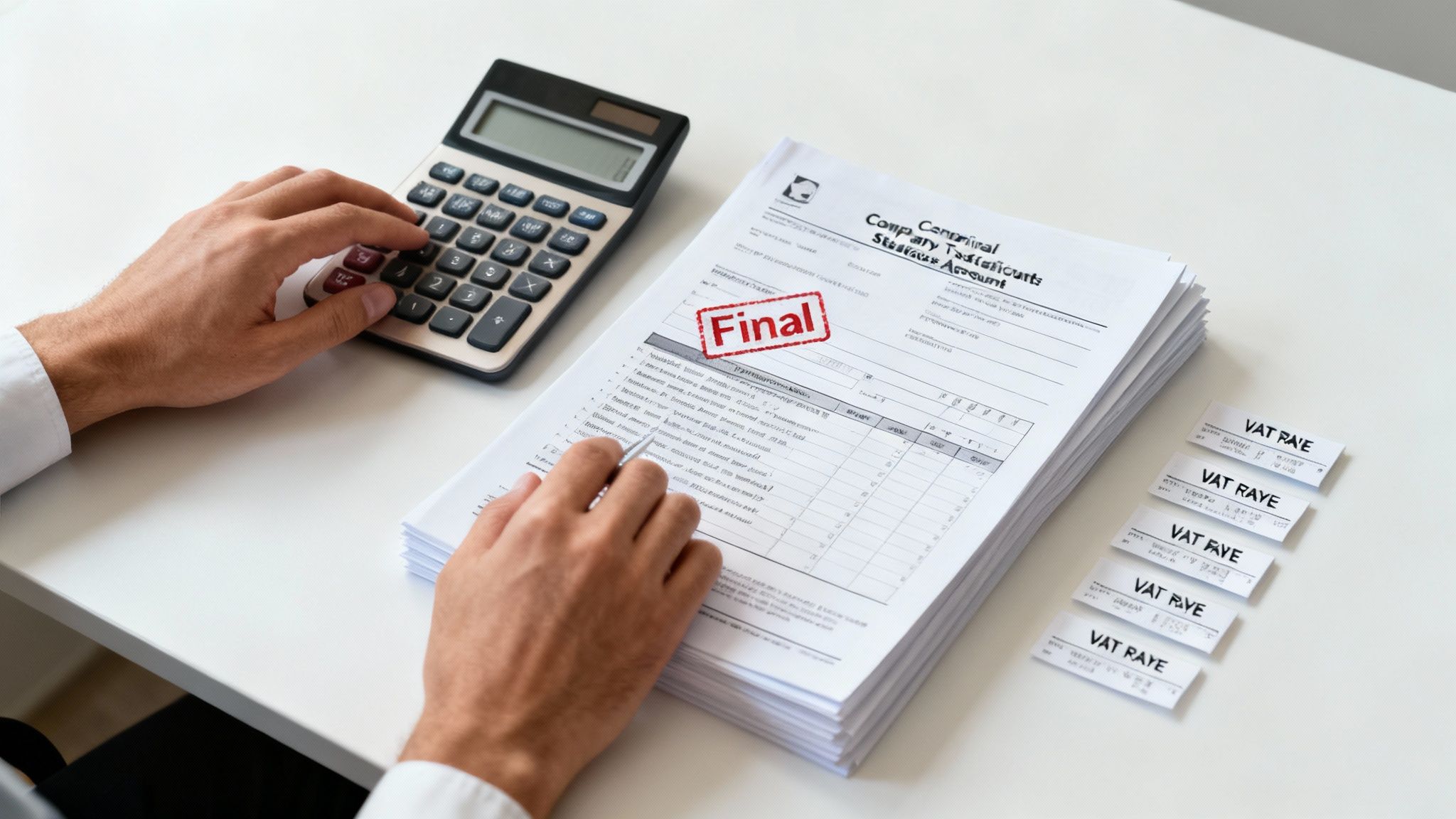

Your first big task is to prepare the final statutory accounts and a Company Tax Return. These aren’t your standard annual filings; they specifically cover the period from the day after your last year-end right up to the date your company officially stopped trading.

It's vital to clearly state on the return that this is the final trading period and the company will be dissolved shortly. This is your formal signal to HMRC that there's no more trading activity to come, which is essential for winding down your tax obligations.

The official government guidance makes it clear that informing HMRC and sorting out your final tax bill are top priorities.

Don’t miss the deadlines. You have to pay any Corporation Tax you owe within nine months and one day of your company’s accounting period end date. Filing these final documents accurately and on time is the only way to avoid any late filing penalties. These final submissions can feel a bit complex, so getting professional help with your company tax returns can offer some much-needed peace of mind.

Once you’ve stopped trading, you need to proactively de-register for other business taxes. If you don't, HMRC will continue expecting returns from you, which will trigger automatic penalties for non-submission even though your company is completely inactive.

These steps aren’t optional. They are a director’s responsibility and are crucial for a clean financial break.

A common oversight I see is directors forgetting to close the company's PAYE scheme. This can lead to months of automated penalty notices from HMRC for failing to file payroll reports, creating a huge amount of unnecessary stress long after they thought the business was wrapped up.

How you take the final funds out of the company has massive tax implications for the shareholders. When a company is formally liquidated, any distributions are usually treated as capital gains, not as income dividends.

Why does this matter? Capital gains are often taxed at a lower rate, and shareholders might be eligible for Business Asset Disposal Relief (BADR). This relief can slash the Capital Gains Tax rate to just 10% on qualifying gains, up to a lifetime limit of £1 million.

On the other hand, if you simply strike the company off without a formal liquidation and the distributed assets are worth more than £25,000, HMRC will treat the whole lot as dividend income. This could easily push a shareholder into a higher tax bracket, with rates jumping as high as 39.35%.

For solvent companies with significant assets left in the bank, this makes a Members' Voluntary Liquidation (MVL) the most tax-efficient route to closure by a long shot.

Winding down a company is a path littered with potential tripwires. Even with the best intentions, a simple oversight can lead to frustrating delays, hefty financial penalties, and sometimes, serious legal trouble for directors. Knowing what these common mistakes are is your best defence for a clean, smooth closure.

One of the most critical errors I see is directors choosing the wrong tool for the job. The line between a solvent strike-off and an insolvent liquidation isn't just a matter of paperwork; it's a legal boundary you absolutely cannot cross.

This is, without a doubt, the single biggest mistake a director can make. If your company can't pay its debts, applying for a strike-off is a serious breach of your duties and can be seen as a deliberate attempt to dodge creditors. When (not if) it’s discovered, Companies House will reject the application, and your creditors can petition to have the company forced into compulsory liquidation.

The personal consequences for directors can be life-altering:

If the company has liabilities it can't clear, a Creditors’ Voluntary Liquidation (CVL) is the only correct and responsible way forward. It protects you from accusations of wrongful trading and ensures creditors are treated fairly under the law.

It’s an easy administrative slip-up, but it has big consequences. When you file the DS01 form to start the strike-off process, the clock starts ticking on a strict seven-day window. In that time, you are legally required to send a copy to every single shareholder, creditor, employee, and any director who didn’t sign the form.

Forgetting to notify even a small creditor will almost guarantee they will object to the dissolution. An objection immediately freezes the entire process, leaving you with lengthy delays while you sort out the problem.

A director's responsibility is to make sure every stakeholder is kept in the loop. This isn't just good manners; it's a legal requirement designed to ensure transparency and stop directors from quietly dissolving a company to escape their obligations.

Shutting the doors with Companies House doesn't mean your relationship with HMRC is over. You are still on the hook for filing final accounts and a Company Tax Return covering the last trading period. Skipping this step triggers automatic penalties for non-filing, which will just keep racking up against the company and create a real mess to untangle later on.

Just as common is forgetting to de-register for VAT and PAYE. If you don't, HMRC will continue to expect returns, leading to more penalties and a lot of unnecessary admin. Finalising your tax affairs properly is essential for a clean break. It’s also crucial for maintaining compliance with regulations like Making Tax Digital for Self Assessment if you plan to continue as a sole trader.

Not all industries are created equal. Some sectors are far more vulnerable to economic headwinds, which can tip a company into insolvency faster than you might expect. Being aware of these trends gives you crucial context when deciding how and when to close your company.

The following table, based on the latest government data, shows the UK industries that have seen the highest rates of insolvency over the past year.

These figures really highlight how things like market conditions and supply chain disruption are hitting certain businesses harder than others. For directors in these fields, it’s a stark reminder to keep a very close eye on the company's financial health.

By steering clear of these common pitfalls, you not only protect yourself from personal liability but also ensure the business you worked hard to build is closed down professionally and ethically. Learning from others' mistakes is the smartest way to make your company's closure straightforward and compliant.

Wrapping up a limited company for good often throws up a lot of last-minute questions. It's a process most directors only go through once, so it’s natural to feel a bit unsure. Getting clear on the key details will help you navigate the final steps with confidence.

Here are a few of the most common queries we hear from directors preparing to close their doors.

The timeline really depends on which route you take. A straightforward strike-off is by far the quicker option. Once you’ve submitted the DS01 form to Companies House, they’ll place a notice in The Gazette, which is the UK’s official public record.

This starts a two-month objection period. If no creditors or other interested parties raise an objection during that time, your company will be formally dissolved soon after. All in, you’re typically looking at about three to four months from start to finish.

Liquidation, on the other hand, is a much more drawn-out affair. A Members' Voluntary Liquidation (MVL) for a solvent company can easily take anywhere from a few months to a year, especially if there are complex assets to sort out and distribute. For an insolvent company going through a Creditors' Voluntary Liquidation (CVL), the process can be just as long while the liquidator works to sell assets and manage creditor claims.

This is a big one, and getting it wrong can be a real headache. As soon as your company is officially dissolved, it legally stops existing. Any assets left behind—including cash sitting in a business bank account—are automatically passed to the Crown.

The technical term for this is “bona vacantia,” which literally means “ownerless goods.”

It is absolutely critical to close your company's bank account and transfer any remaining funds before the company is struck off the register. Trying to reclaim money from the Crown is a long, difficult, and expensive process that you want to avoid at all costs.

Make sure emptying and formally closing the bank account is one of the final items on your checklist.

One of the core protections of a limited company structure is that it separates your personal finances from the business's liabilities. For the most part, you will not be held personally responsible for company debts when you close it down.

However, that protection isn't bulletproof. There are specific situations where directors can find themselves personally liable:

Your best defence is to act responsibly and follow all the correct procedures for the closure. If you have any doubts about your situation, it’s always wise to get professional advice.

Closing your company correctly is the final act of responsible directorship. For expert guidance on final accounts, tax obligations, and ensuring a clean closure, GenTax Accountants is here to help. Visit us at https://www.gentax.uk to learn how we can support you.